Since Kayleigh Caamaño and her husband, Jann, opened a pizza restaurant three years ago in Stephenville, Texas, filling open positions has never been an issue.

“We’ve always had a problem getting good people, but we’ve never had a problem hiring people,” Caamaño said. That’s partly because the restaurant is located just about a mile away from Tarleton State University’s campus, where some 14,000 undergraduates students were enrolled last fall.

“Now it’s changed to where overall people just aren’t applying,” she said, or the few who do apply ghost them after interviews or quit before they even start working.

Caamaño’s experience aligns with what many other restaurants owners have likely been facing.

“

In the food services industry specifically, payrolls declined by 42,000 in August

”

Last month there were no new jobs created across the entire leisure and hospitality industry, according to the jobs report published on Friday. In total, some 235,000 jobs were added in the U.S. last month — far below the 720,000 jobs economists had forecast.

In the food services industry specifically, payrolls declined by 42,000 in August.

Restaurants struggled to recruit and retain employees before COVID-19

Even before the pandemic, recruiting and retaining employees “had been the industry’s top challenge for many years,” said Hudson Riehle, senior vice president for research at the National Restaurant Association, a trade group that represents more than 380,000 restaurants. Long hours and challenging work conditions come with relatively low pay for restaurant servers; the median wage was $24,190 a year in 2020, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

That challenge has intensified as more Americans have gotten vaccinated and started to dine out again. “As consumers have stepped up their restaurant usage, industry traffic has increased, creating a greater need for employees,” he told MarketWatch. In January, 8% of restaurant operators rated recruitment and retention of workforce as their top challenge; by June that number had risen to 75%, the highest level ever recorded, according to an August report by the National Restaurant Association.

High demand for workers in other industries, caregiving responsibilities and safety concerns associated with COVID-19 are collectively holding back workers from taking jobs in the restaurant sector, Riehle said.

Economists are blaming the lackluster August jobs report — and the fact that no new jobs were added in the leisure and hospitality industry, which includes restaurants — primarily on the highly transmissible delta strain of COVID-19.

“It’s plausible that many employees decided to ‘sit out’ the delta spike and use the time to search for jobs that offer better pay and safer work conditions,” Aneta Markowska and Thomas Simons, economists at Jefferies, said in a note on Friday, referring to the leisure and hospitality sector.

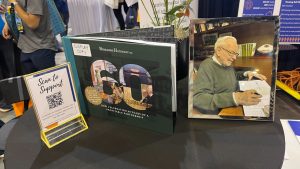

Caam’s is located near a college campus, which usually makes it easy to recruit employees, but lately hardly anyone has applied for five open positions, said co-owner Kayleigh Caamaño.

Photo courtesy of Kayleigh Caamaño

“We have been hard-pressed to help source [talent] into the hospitality industry,” said Richard Wahlquist, president and CEO of the American Staffing Association, a member-based organization representing recruiters and hiring managers.

“

‘It’s plausible that many employees decided to ‘sit out’ the delta spike and use the time to search for jobs that offer better pay and safer work conditions’

”

— Aneta Markowska and Thomas Simons, economists at Jefferies

“The delta variant has put a dampener on labor supply,” he told MarketWatch. Members that he works with are “seeing more hesitancy to come back into the labor market than they would have expected.”

Caamaño is skeptical that delta is the reason she and her husband can’t fill job openings

“A lot of people around here don’t take COVID seriously,” Caamaño said. College kids may be deterred from working at the restaurant because of COVID, she said, but it doesn’t seem likely to her, given that “they don’t hesitate to still go out to eat or go to the bars.”

Currently, she and her husband are looking to hire a food runner, bartender, pizza cook, kitchen prep cook and a dishwasher. Her team of 11 employees has managed to get by without the additional employees over the course of this year, she said.

“

‘My husband and I are trying to wrap our brains around it, but we really can’t figure out why people don’t need to work.’

”

— Kayleigh Caamaño, co-owners of Caam’s

But recently the restaurant had to stop serving lunch temporarily on weekdays while one employee was out on vacation and two others couldn’t work after they were exposed to someone who had tested positive for COVID-19.

Caamaño hasn’t considered raising the pay for the open positions; the restaurant already pays more than neighboring establishments because it allows employees to keep their tips on top of their hourly wages, she said.

She also doubts that extra unemployment benefits are holding back people from applying for jobs, because Texas was among 26 states that cut unemployed people off from the extra $300 a week in unemployment benefits early, before they expire this weekend.

“My husband and I are trying to wrap our brains around it but we really can’t figure out why people don’t need to work,” Caamaño said.

Also read: ‘It feels like they just flipped a coin’: Restaurants struggle after missing out on bailout funds

This post was originally published on Market Watch