From wildfires to floods, hurricanes to heat, the effects of climate change on our communities are well-known, and widely expected to get worse.

But as participants in the municipal debt market are starting to realize, there are no bond vigilantes to enforce discipline on state and local government issuers. A new study confirms that notion, showing that investors haven’t yet begun to demand any premium for bonds that may be more at risk due to extreme weather.

That means that as weather becomes more volatile, things may have to change: either municipalities will pay more to borrow, or state governments and Washington may increasingly pick up the tab to make bondholders whole.

The report, from climate analytics firm risQ, Inc. analyzed the yields on about 800,000 municipal bonds issued between 2006 and 2021, accounting for about $2.5 trillion of the $3.9 trillion outstanding. “This is an era,” the report notes, “where it is reasonable to assume climate risk was broadly recognized as a potential issue.”

Earlier coverage: Climate risk is hitting home for state and local governments

The research process involved making an estimate of the expected yield of all the bonds in the data set, based on factors that are known to influence yield, such as duration of the bond, type of issuer, and so on. It omitted climate risk as an input. Then, the researchers layered a proprietary climate risk score over the bonds, demonstrating that there is no correlation between climate and any additional risk premia for bonds that was unexplained by the other drivers.

Source: risQ, Inc.

The researchers then reran the same model, using only bonds issued between 2017 and 2021, noting that “physical climate risk came to the forefront of the collective awareness of the market after 2017’s hurricane season,” which remains the costliest on record.

But they come to the same conclusion with the second experiment: climate doesn’t influence yields.

In addition to the data analysis they perform, risQ analysts have some important takeaways about why the municipal market hasn’t yet reckoned with climate risk.

Among them is the old saw that muni bonds rarely default. As they note, “compared to other asset classes, municipal bonds have indeed been historically less risky. Because of this, systemic risk in general (climate and otherwise) has not been nearly as central a concern to the world and culture of municipal bonds as it has been to insurance or mortgage-backed security markets.”

Another is a belief that climate hasn’t historically caused defaults, an argument “that we hear less and less of as the climate crisis worsens,” the report notes. They call climate risk “a ‘frog in a pot of boiling water’ situation, wherein systemic risk is significantly underestimated, and the heat will at least turn up gradually, and maybe abruptly.”

What does this mean for investors?

Among other things, risQ repeats some of the themes MarketWatch has reported on in recent months: investors should be aware that the municipal market may have risks that are camouflaged by lopsided supply and demand, issuers with little incentive (so far) to disclose their challenges, and ratings firms and regulatory agencies that may not be as proactive as necessary.

The risQ report concludes with one example of a recent climate catastrophe: the fire in Paradise, California, in 2018, where nearly 90% of the town was destroyed and 90% of the population forced to leave. Despite that, Paradise was able to pay its bondholders, both because of state legislation that allowed California to step in and backfill payments, and because the state was able to secure direct federal aid.

As MarketWatch has previously reported, some observers think the municipal market may not be able to continue to rely on state and federal bailouts, particularly as “hundred year” weather events become every-year occurrences. By the time the frog realizes he’s in hot water, in other words, it may be too late.

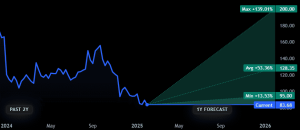

“Bond issuers will need to prepare for potential ‘sticker shock’ in many cases — yields don’t reflect climate risk yet, but this is almost certainly a matter of when, not if,” risQ writes. But the sooner they take proactive steps, the better: addressing the problem is not just good for the overall market, but is considered a “credit positive” as well.

This post was originally published on Market Watch